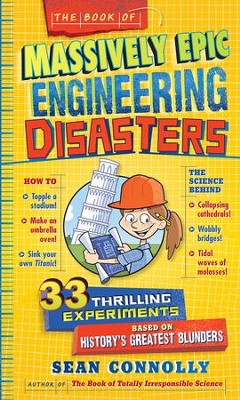

The Book of Massively Epic Engineering Disasters:

33 Thrilling Experiments Based on History's Greatest Blunders

by Sean Connolly

I wrote a blog post previously with my planning notes when doing this block on Zoom. Now I get to do it IRL with a group of students!

For each disaster I'll share my up-to-date notes and some photos. Today we learned about the Tay Bridge disaster in 1879 (Dundee, Scotland).

- recall last week's disaster (The Leaning Tower of Pisa)

- discuss our pendulum explorations, look at the formula for velocity and note that mass is NOT in it!

- discuss our experiments with center of mass and relate them to the efforts to free the enormous 'Ever Forward' cargo ship stuck in the Chesapeake Bay

- explain some of the efforts they've made to free the ship and answer questions about why they can't just unload it to lighten it (very tricky safety-wise because it would unbalance the ship... plus it's a logistical nightmare)

Fortunately, my neighbor wrote up a good explanation of how port cranes are different from the cranes they would potentially have to use with the ship being stuck in the Bay, and I shared some of what he wrote with the class:

VIDEO: Gigantic Cranes Maneuvering Under Bridges to Baltimore

The Maritime Executive

"Ports have huge cranes (you can see them in the video above) which have been developed to only move containers. They tower over the ship bringing them to port. These cranes have automatic latching systems to grab the containers and move them to and from the narrow confines of the cargo ship to the quayside. It takes 4-8 of these working nonstop anywhere from one to several days to shuffle containers around so the ship can weigh anchor for their next port of call. The 'Ever Forward' probably has in excess of 6000 containers (normal containers are 20 or 40 ft long) if not significantly more.

"The way to offload containers from a ship not at a port with the prior-mentioned facilities is typically with a barge and regular crane such as one might see working on roadsides on any given day of the week. Attaching & detaching the containers is done manually and all movement is completed through a radio as there's no way the crane operator can see where the pick is at. It's an awfully slow process that they try to use only as a last resort because it's so slow in movement of the containers. Lightening the load (there's 6k+ of them remember?) is going to take quite a few containers to make a difference and all those offloaded containers will still need to make it to their eventual destination. They'd much rather do most anything rather than moving containers because, on a container ship specifically, that is probably one of the slowest options."

Tugboats and anchored pulling barges are the first things they'll try, along with dredging. If you're really interested in this, here's a more detailed video (and the comments below are thoughtful and interesting).

- do Capsized! How Sailboats Stay Upright experiments to learn more about how center of mass applies to boats

- for each child:

three corks

two rubber bands

three toothpicks

craft foam

aluminum foil

scissors

identical nails or screws that are roughly the length of your corks (exactly how many you need will vary depending on their size)

You will also need a sink, bathtub, or a large container you can fill with water. The container should be deeper than the length of your nails/screws.

- read "The Tay Bridge Disaster" information from The Book of Massively Epic Engineering Disasters, pp. 49-53

- do experiment #8 "Wind Load"

- for each team (set up two):

three wooden blocks of the same size

hair dryer

four nail files

piece of chalk

black construction paper (optional)

We set this up on the concrete garage floor and used the chalk to mark the placement of the bridge and the placement of the hair dryer, so that we could keep that the same between the trials. This was a student's idea and it was a great one! You could also give each team a piece of black construction paper to stand their bridge on.

We used Glue Dots because they are instant and permanent and we didn't have to wait for the glue to dry. However, one child noted that they might melt from the heat of the dryer and so let go. This could be a downside, or you could use it to your advantage. The Tay Bridge failed at the lug nuts due to metal fatigue (and the bridge came apart just like it was being unzipped), so you could compare it to Glue Dot failure.

- do experiment #8 "Snap, Crackle..."

- for each child:

a paper clip

You could also do this with an old metal coat hanger, but it is harder to bend (and gets much hotter at the point where it breaks).

- pass out Science Club notebooks, have each child draw and write notes about his/her favorite experiment or about the disaster itself

This post contains affiliate links to materials I truly use for homeschooling. Qualifying purchases provide me with revenue. Thank you for your support!

Immersive Experience

Immersive Experience Immersive Experience

Immersive Experience

No comments:

Post a Comment