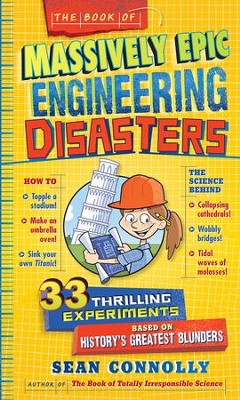

The Book of Massively Epic Engineering Disasters:

33 Thrilling Experiments Based on History's Greatest Blunders

by Sean Connolly

I wrote a blog post previously with my planning notes when doing this block on Zoom. Now I get to do it IRL with a group of students!

For each disaster I'll share my up-to-date notes and some photos. In this session we learned about the sinking of the Titanic in April 1912.

- recall last week's disaster (Tay Bridge) and look at facts and images from the "Disaster Above the River Tay" article in "The Highlander" magazine Jan/Feb 2020 issue (thank you to the parent who brought this in to share!)

- review our previous exploration of center of gravity & discuss Egg Spinning

- sink/float explorations (walk around the yard and find one think you think will sink and one thing you think will float, bring them back and test them, organize sink/float items into two piles)

sink pile - rocks

- why do things sink? the children agreed it was because they are heavy

- is it possible to have two things that have the same mass but one thing sinks and one thing floats? some children said yes and some said no

- look at two items which both have a mass of 11 grams

Teifoc brick roofing tile sinks

- explain formula for density

- shake Ocean Bottle vigorously, watch how the oil separates back out and floats on top of the water even when the bottle is placed upside down (vegetable oil has a density of 0.92

g/mL, water has a density of 1.0 g/mL)

- discuss how density relates to why rotten eggs float

- do Floating and Sinking Pop Cans Experiment

-

for each group (set up one):

large bucket or container

water

variety of unopened 12 oz soda cans, some regular and some diet

Note: I discovered that it is important to use newly purchased & fresh soda!

When I first did this experiment several years ago I was so impressed with it and I thought, well, I'll just hang on to these cans of soda. Put them in with my experiment things. Soda doesn't require refrigeration so they won't go bad. Why spend the money to buy them again? However, I discovered -- much to my dismay -- that several of the brands of soda (all DIET, notably) had leaked all over the floor of the closet in the Science Room. The cans appeared to be completely unopened but they were empty and there were liquid stains and mold all over the brown paper bag and my beautiful hardwood floor. It is a mystery to me as to how they leaked, but they did.

So, then I thought, I'll still keep them (I really hate to waste money) and I'll just have the sense to line the box with plastic next time. That way if they leak, no problem. However, of the cans which still seemed full, one which contained regular soda floated when we did the experiment, and it shouldn't have. Only the diet drinks should float. This caused our experiment to have failed results. My conclusion? Be sure to buy your soda cans each time you do this experiment and just pour them out and recycle them afterwards.

- read The Titanic: Lost... and Found by Judy Donnelly

- do experiment #11 "Overflow!" from The Book of Massively Epic Engineering Disasters

-

for each group (set up two):

large bucket or container

water

metal mini muffin pan

pitcher, plastic bottle, or elephant watering can

He suggests a plastic ice cube tray, but I can't get ours to sink because of the plastic material. I think a metal mini muffin pan gives better results.

- do How Much Weight Can Aluminum Foil Boats Float? experiment

-

for each group (set up two):

large bucket or container

water

aluminum foil

ruler

cellophane tape

100 pennies

2 lb dry rice

measuring cup

calculator

paper and pencil

paper towels

This experiment is the next level above "who can make an aluminum foil boat design that holds the most weight?" which most of my students had done before. Here we are actually calculating the density of our boat right before it sinks. It should be very close to the density of water (1.0 g/mL). When you add that one additional penny, the density of your boat is suddenly greater than the density of water and whammo, down you go. In order to caculate the density of your boat, you need its volume, which you measure by filling the boat with dry rice. Measure the dry rice in mL. You also need its mass before sinking, which you measure by counting the number of pennies that are in it after it sinks, then subtracting one penny, then multiplying that number of pennies by 2.5. Each penny weighs 2.5 grams. Divide the mass by the volume, and you have the density! Don't forget to measure the mass of the boat itself and add it to your penny total. You can see on our notes that we forgot about the boat initially, then added it in and recalculated.

This experiment is interesting and -- although it is a real pain to lift up, and pour from, a fragile aluminum foil boat full of hundreds of tiny grains of rice without breaking the darn thing -- I think it is worth doing. For one thing, you are actually showing the students how to calculate density, which they appreciate. The other is that it led us to a really specific discussion of sources of error. The experiment description at Science Buddies states,

- "...both hulls should roughly have a density of 1 gram per cubic centimeter right before sinking. (Your densities may not have been exactly this, but may have ranged between 0.7 to 1.3 grams per cubic centimeter. Sources of error that you could try to get rid of to give you an answer closer to the actual density of water include more accurately calculating the volume of each hull, using something smaller than pennies, and including the hull's weight in your calculations.)"

We really noticed that something went wrong with the numbers at Big Boat. It was interesting to think about what might have happened, and what we would do differently if we did it again. At the time I figured they were moving too quickly and weren't placing the pennies in evenly. But just now, in the process of typing up these notes, I suddenly remembered that Big Boat was so heavy when it was full of two cups of rice that its prow split wide open as I was lifting it up in order to pour the rice into the measuring cup. The prow had to be repaired with tape. Maybe this structural weakness is why it sunk earlier than it should have. I think it went down before its time.

- pass out Science Club notebooks, have each child draw and write notes about his/her favorite experiment or about the disaster itself

- answer questions and share facts from 882 1/2 Amazing Answers to Your Questions About the Titanic by Hugh Brewster

This post contains affiliate links to materials I truly use for homeschooling. Qualifying purchases provide me with revenue. Thank you for your support!

Immersive Experience

Immersive Experience Immersive Experience

Immersive Experience

No comments:

Post a Comment